Camille Fallet

With works by: Julia Curtin, Walker Evans, Camille Fallet, George Georgiou, Darren Harvey-Regan, Lisa Kereszi, Justine Kurland, Sherrie Levine, Ute Mahler & Werner Mahler, Michael Mandiberg, James Nares, Jessica Potter, Patrick Pound, RaMell Ross, Mark Ruwedel, Anastasia Samoylova, Bryan Schutmaat, Stephen Shore, Vanessa Winship

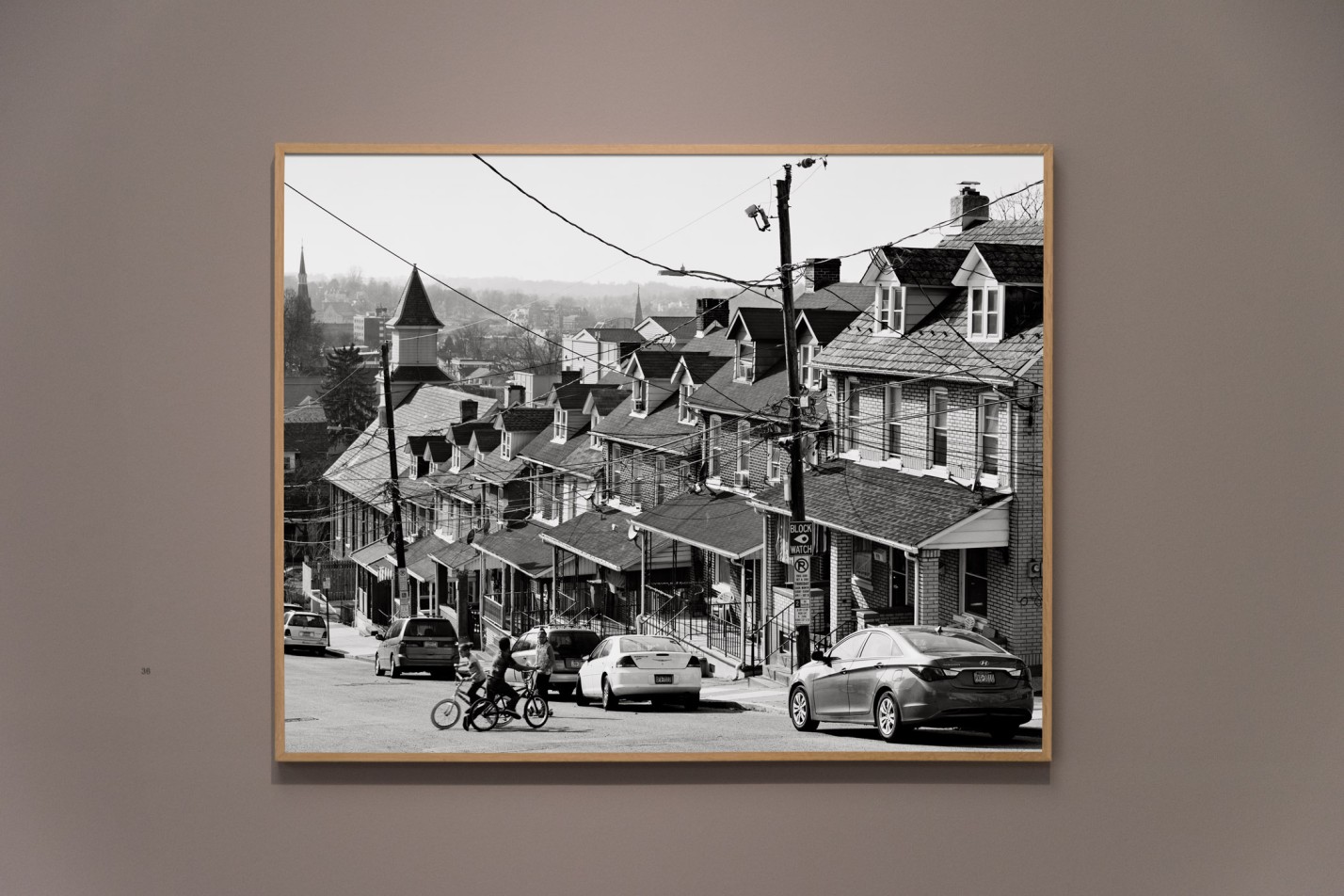

Of all the celebrated photographers of the last century, the one who is most relevant today, and the one with the widest influence, is Walker Evans (1903 – 1975). Some of his images are among the best known in the history of the medium. Direct and generous, analytical, yet lyrical, carefully composed, but unforced, the ways in which he photographed left the door open for countless others to follow. He was also concerned with the idea that photographic meaning is related to context, text and relations between images, whether on the gallery wall or on the pages of books and magazines. To be in control of one’s photographs means being in control of how they are presented and circulated in the world. So, as well as being a remarkable image maker, Evans was also an editor, writer and designer. Walker Evans Revisited brings together two kinds of response from contemporary artists and photographers. Firstly, there is the continuation and extension of Evans’ ways of photographing everyday life. Secondly, the exhibition presents a variety of projects by artists responding very directly to particular images and projects by Evans. These range from appropriation and collage, to re-imaginings and homage.

Of all the celebrated photographers of the last century, the one who remains the most relevant today, and the one with the widest influence, is Walker Evans (1903-1975). Some of his images, made in what he famously called the “documentary style”, are among the best known in the history of the medium. Direct and generous, analytical yet lyrical, carefully composed but unforced, the ways in which he photographed left the door open for countless others to follow.

For a while, Evans’ reputation rested on the photographs he had made in the southern parts of the USA in the 1930s. Images by Evans, Dorothea Lange, Jack Delano and others became a kind of visual mythology of that era. But Evans’ achievement was wider and deeper than that. He worked with every camera format and photographed many subjects in many different ways, from surreptitious street shots of passers by, to meticulous and exacting studies of architecture. He embraced new artistic and technical developments in photography, and at the end of his life he explored what could be done with a Polaroid camera. What united it all was a deep interest in, and affection for, the look and feel of everyday life. Not the latest fashions, designs, or buildings, and not the oldest either. He was not nostalgic, but understood the consequences of discarding the past too quickly, and prizing novelty too highly. In a culture increasingly obsessed with the new, Evans cherished things that were standing the tests of time and complex life, be it a face or the facade of a warehouse.

But this is only half the reason why Evans remains a touchstone for so many of us today. He was also concerned with the idea that photographic meaning is related to context, text, and relations between images, whether on the gallery wall, or on the pages of books and magazines. To be in control of one’s photographs means being in control how they are presented and circulated in the world. So, as well as being a remarkable image-maker, Evans was also an editor, writer and designer. In this way he could pay close attention to all the elements that shape the ways his work was encountered, producing arrangements of images and words with resonances far greater than the individual parts.

Evans orchestrated his exhibitions with great care. In 1938 he was the first photographer to be offered a solo show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. The night before opening, he locked himself into the galleries to ensure the arrangement of his pictures was as he wanted. For Evans, the exhibition itself was as much the medium as the images. The publication made on the occasion of that show, American Photographs, was also very carefully considered, the pictures unfolding over the pages through association and repetition. Its format was small and its printing was straightforward, avoiding the preciousness of the ‘art book’. It remains one of the most ambitious and influential photographic books, and has been reprinted several times.

Evans also understood that images are often appropriated and re-used in different ways. We are all familiar with this today, but Evans was exploring it from very early in his career. For example, in 1933 he produced a sequence of photographs for Carleton Beals’ book The Crime of Cuba, a study of the country’s corrupt American-backed Machado regime. They are gentle and observant lyrical street shots, but Evans disrupts the sequence with shocking images of murdered dissidents, and imprisoned students. Evans did not make these photographs: be bought them from a Havana newspaper office, knowing how he was going to deploy them in a new way.

Evans had great interest in anonymous and vernacular culture. He collected hand made road and shop signs, and amassed around nine thousand popular American postcards. He felt the cards made between 1890 and 1910 provided a better record of North American society than any official documents. When nobody else was interested, he championed these postcards in illustrated features for magazines.

Apart from a short period working for the US Government in the mid-1930s, Evans never joined a photographic agency. He grasped very clearly that if photographers make images and simply hand them over to an agency for distribution, they have little hope of overseeing what happens to them. In his two decades working for Fortune magazine (1945-1965) Evans got himself into a position where he could set his own assignments, shoot, edit, write and lay out his own pages. Fortune was a magazine of business and industry, but he produced photo-essays about overlooked aspects of life: anonymous citizens, the unemployed, everyday objects, small shops, vernacular signage, and forgotten architecture. He had great disdain for much of what magazine culture was about - celebrity, consumerism and easy spectacle - but felt that a more intelligent and reflective popular culture was worth fighting for.

We live in a culture where images often move around so freely, particularly online, that it often seems as if meaning is about to fall into chaos. This is why control has become a central concern for serious photographers. Evans’ books are still models of what an image sequence can do, while his working life in the difficult environment of American commercial culture remains a beacon of independent thinking. Sooner or later, all photographers face the question of what happens to their images after they have taken them. Evans is an example for us all.

Walker Evans Revisited brings together two kinds of response to his work by contemporary artists and photographers. Firstly, there is the continuation and extension of his manner of photographing everyday life. In North America and Europe in particular, Evans continues to provide the model for many observational photographers working in the rejuvenated and expanded field of documentary work. Secondly, the exhibition presents a range of projects by artists responding very directly to particular images and projects by Evans. These range of appropriation and collage, to re-imaginings and homage.

David Campany