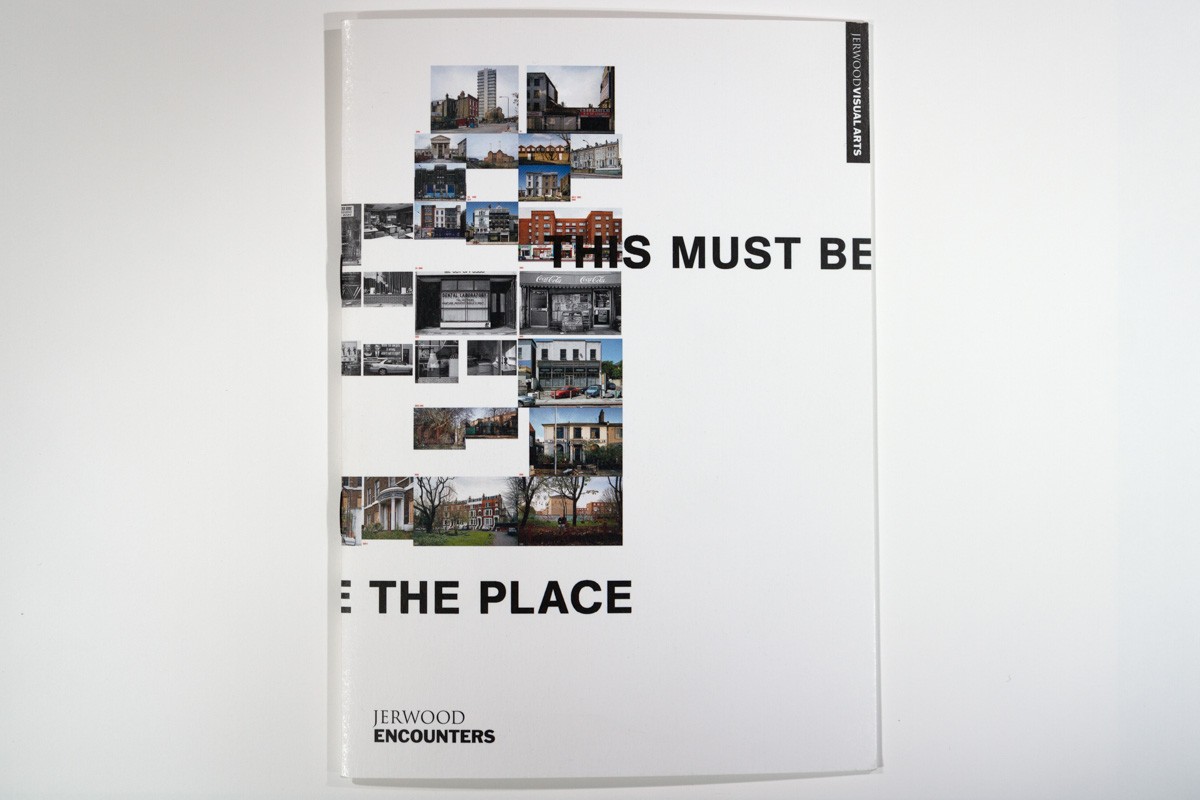

Camille Fallet

This Must Be the Place JERWOOD SPACE, LONDON, 2010

Curated by David Campany

Works by Camille Fallet, Mimi Mollica, Xavier Ribas, Eva Stenram, Lillian Wilkie, Tereza Zelenkova and David Campany

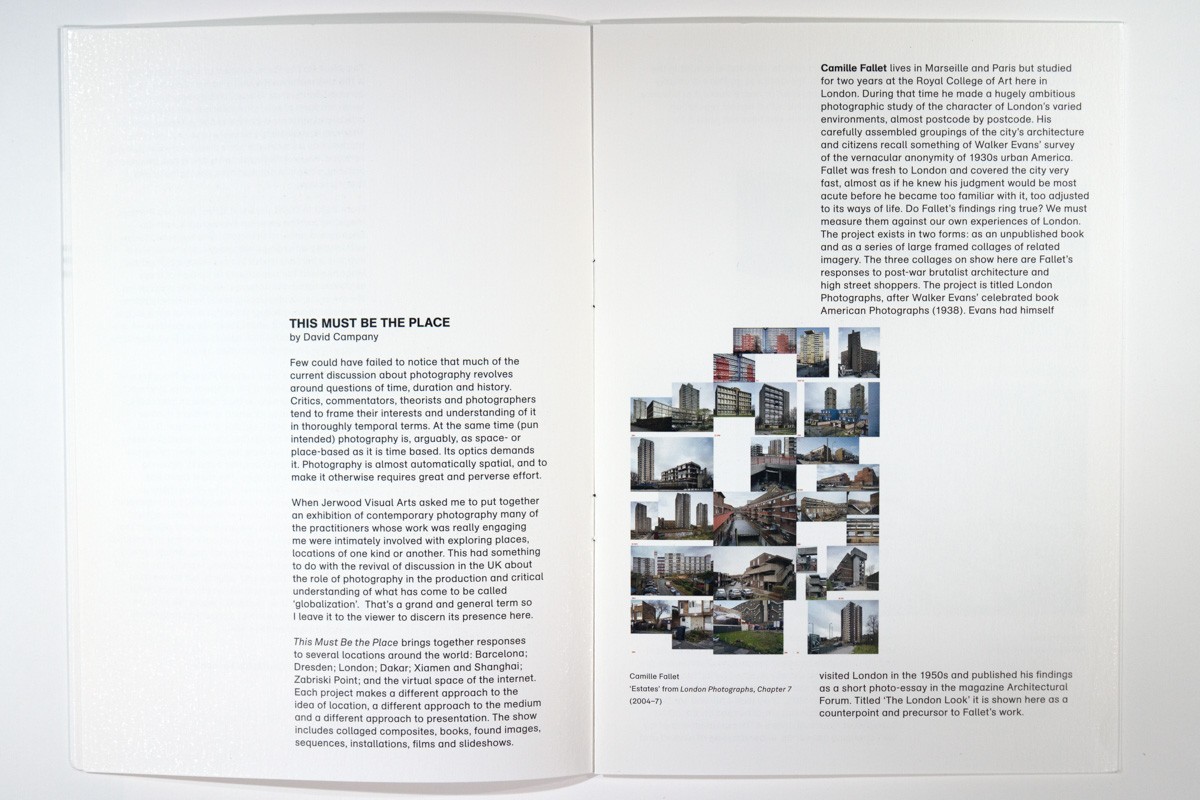

Few could have failed to notice that much of the current discussion about photography revolves around questions of time, duration and history. Critics, commentators, theorists and photographers tend to frame their interests and understanding of it in thoroughly temporal terms. At the same time (pun intended) photography is, arguably, as space- or place-based as it is time based. Its optics demands it. Photography is almost automatically spatial, and to make it otherwise requires great and perverse effort. When the Jerwood Space asked me to put together an exhibition of contemporary photography many of the practitioners whose work was really engaging me were intimately involved with exploring places, locations of one kind or another. This had something to do with the revival of discussion in the UK about the role of photography in the production and critical understanding of what has come to be called ‘globalization’. That’s a grand and general term so I leave it to the viewer to discern its presence here. This Must Be the Place brings together responses to several locations around the world: Barcelona, Dresden, London, Dakar, Xiamen and Shanghai, Zabriski Point, and the virtual space of the internet. Each project makes a different approach to the idea of location, a different approach to the medium and a different approach to presentation. The show includes collaged composites, books, found images, sequences, installations, films and slideshows. Camille Fallet lives in Marseille and Paris but studied for two years at the Royal College of Art in Kensington. During that time he made a hugely ambitious photographic study of the character of London’s varied environments, almost postcode by postcode. His carefully assembled groupings of the city’s architecture and citizens recall something of Walker Evans’ survey of the vernacular anonymity of 1930s urban America. Fallet was fresh to London and covered the city very fast, almost as if he knew his judgment would be most acute before he became too familiar with it, too adjusted to its ways of life. Do Fallet’s findings ring true? We must measure them against our own experiences of London. The project exists in two forms: as an unpublished book and as a series of large framed collages of related imagery. The three collages on show here are Fallet’s responses post-war brutalist architecture and high street shoppers. The project is titled London Photographs, after Walker Evans’ celebrated book American Photographs (1938). Evans had himself visited London in the 1950s and published his findings as a short photo-essay in the magazine Architectural Forum. Titled the ‘The London Look’ it is shown here as a counterpoint and precursor to Fallet’s work.

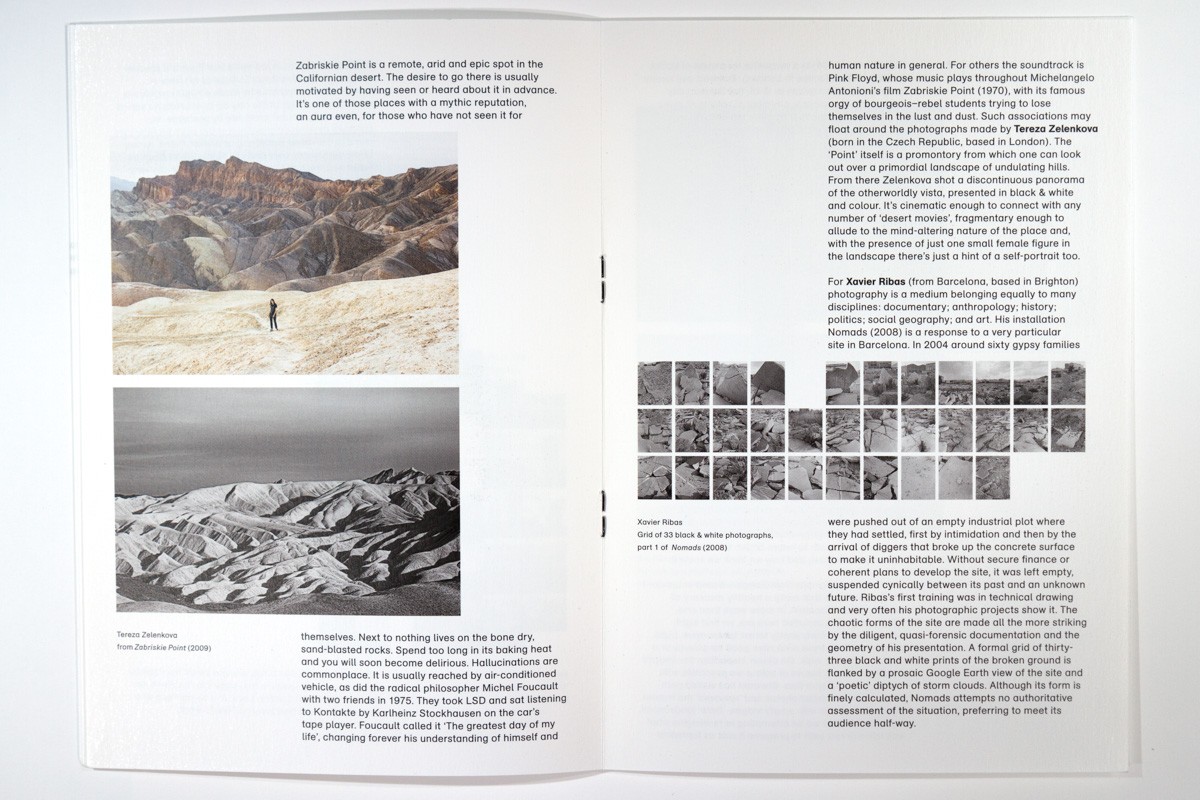

Zabriskie Point is a remote, arid and epic spot in the Californian desert. The desire to go there is usually motivated by having seen or heard about it in advance. It’s one of those places with a mythic reputation, an aura even, for those who have not seen it for themselves. Next to nothing lives on the bone dry, sand-blasted rocks. Spend too long in its baking heat and you will soon become delirious. Hallucinations are commonplace. It is usually reached by air-conditioned vehicle, as did the radical philosopher Michel Foucault with two friends in 1975. They took LSD and sat listening to Kontakte by Karlheinz Stockhausen on the car’s tape player. Foucault called it ‘The greatest day of my life’, changing forever his understanding of himself and human nature in general. For others the soundtrack is Pink Floyd, whose music plays throughout Michelangelo Antonioni’s film Zabriskie Point (1970), with its famous orgy of bourgeois–rebel students trying to lose themselves in the lust and dust. Such these associations may float around the photographs made by Tereza Zelenkova (born in the Czech Republic, based in London). The ‘Point’ itself is a promontory from which one can look out over a primordial landscape of undulating hills. From there Zelenkova shot a discontinuous panorama of the otherworldly vista, presented in black & white and colour. It’s cinematic enough to connect with any number of ‘desert movies’, fragmentary enough to allude to the mind-altering nature of the place and, with the presence of just one small female figure in the landscape there’s just a hint of a self-portrait too.

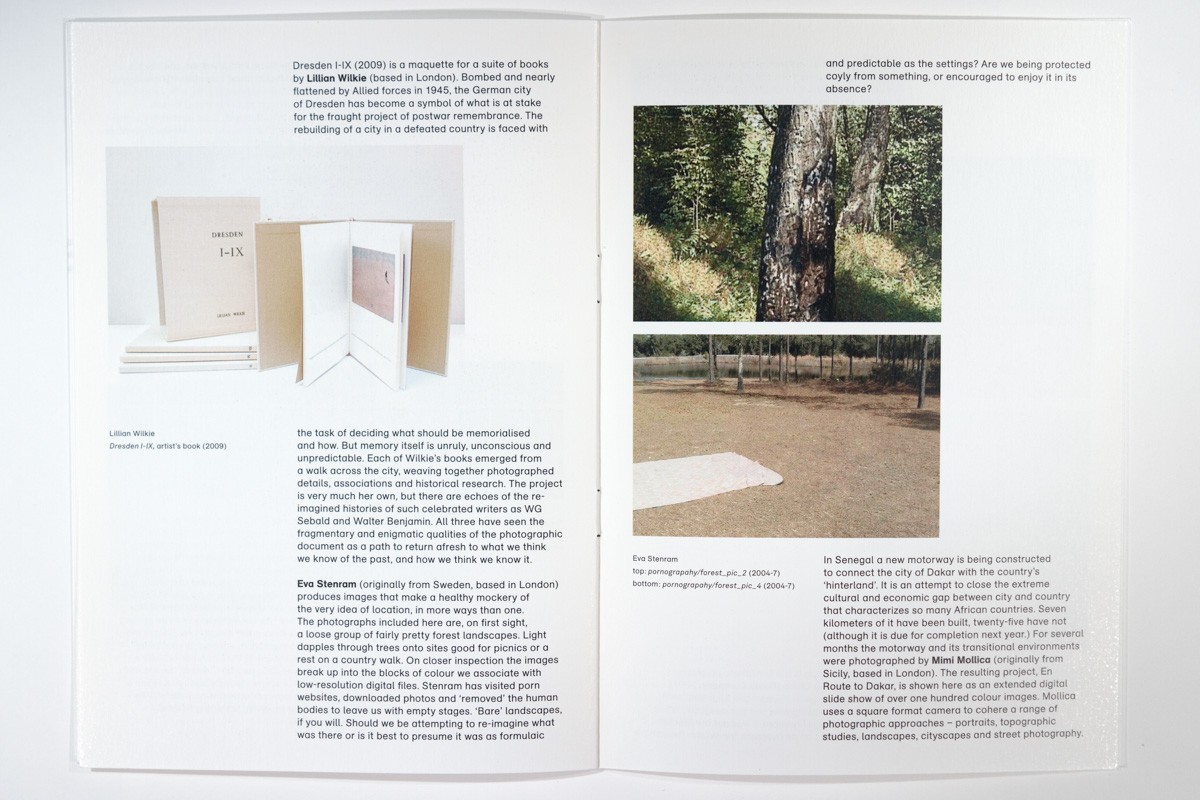

For Xavier Ribas (from Barcelona, based in Brighton) photography is a medium belonging equally to many disciplines: documentary, anthropology, history, politics, social geography and art. His installation Nomads (2008) is a response to a very particular site in Barcelona. In 2004 around sixty gypsy families were pushed out of an empty industrial plot where they had settled, first by intimidation and then by the arrival of diggers that broke up the concrete surface to make it uninhabitable. Without secure finance or coherent plans to develop the site, it was left empty, suspended cynically between its past and an unknown future. Ribas’s first training was in technical drawing and very often his photographic projects show it. The chaotic forms of the site are made all the more striking by the diligent, quasi-forensic documentation and the geometry of his presentation. A formal grid of thirty-three black and white prints of the broken ground is flanked by a prosaic Google Earth view of the site and a ‘poetic’ diptych of storm clouds. Although its form is finely calculated, Nomads attempts no authoritative assessment of the situation, preferring to meet its audience half-way.

Xavier Ribas, Grid of 33 black & white photographs, Part 1 of Nomads (2008) Dresden I-IX (2009) is a maquette for a suite of books by Lillian Wilkie (based in London). Bombed and nearly flattened by Allied forces 1945, the German city of Dresden has become symbol of what is at stake for the fraught project of postwar remembrance. The rebuilding of a city in a defeated country is faced with the task of deciding what should be memorialised and how. But memory itself is unruly, unconscious and unpredictable. Each of Wilkie’s books emerged from a walk across the city, weaving together photographed details, associations and historical research. The project is very much her own but there are echoes of the re-imagined histories of such celebrated writers as WG Sebald and Walter Benjamin. All three have seen the fragmentary and enigmatic qualities of the photographic document as a path to return afresh to what we think we know of the past, and how we think we know it.

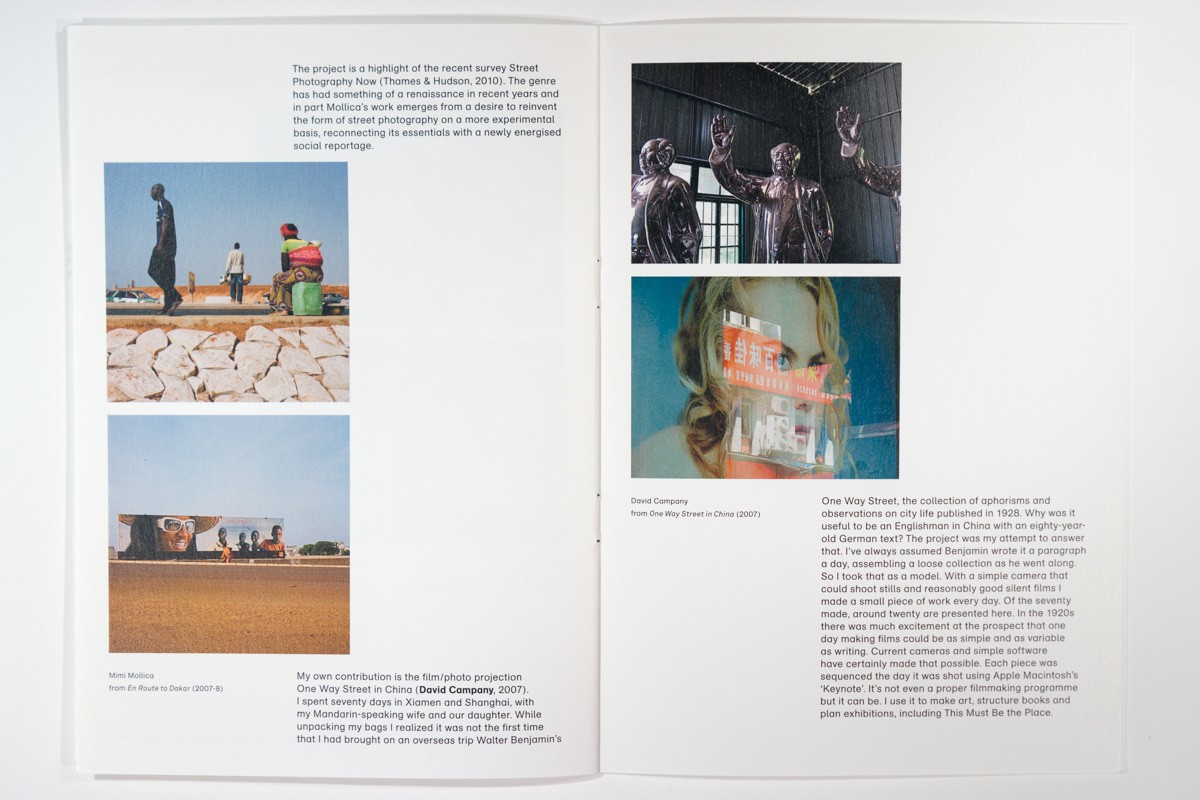

Lillian Wilkie, Dresden I-IX, artist’s book (2009) Eva Stenram (originally from Sweden, based in London) produces images that make a healthy mockery of the very idea of location, in more ways than one. The photographs included here are, on first sight, a loose group of fairly pretty forest landscapes. Light dapples through trees onto sites good for picnics or a rest on a country walk. On closer inspection the images break up into the blocks of colour we associate with low-resolution digital files. Stenram has visited porn websites, downloaded photos and ‘removed’ the human bodies to leave us with empty stages. ‘Bare’ landscapes, if you will. Should we be attempting to re-imagine what was there or is it best to presume it was as formulaic and predictable as the settings? Are we being protected coyly from something, or encouraged to enjoy it in its absence?

In Senegal a new motorway is being constructed to connect the city of Dakar with the country’s ‘hinterland’. It is an attempt to close the extreme cultural and economic gap between city and country that characterizes so many African countries. Seven kilometers of it have been built, twenty-five have not, although it is due for completion next year. For several months the motorway and its transitional environments were photographed by Mimi Mollica (originally from Sicily, based in London). The resulting project, En Route to Dakar, is shown here as an extended digital slide show of over one hundred colour images. Mollica uses a square format camera to cohere a range of photographic approaches – portraits, topographic studies, landscapes, cityscapes and street photography. The project is a highlight of the recent survey Street Photography Now (Thames & Hudson, 2010). The genre has had something of a renaissance in recent years and in part Mollica’s work emerges from a desire to reinvent the form of street photography on a more experimental basis, reconnecting its essentials with a newly energised social reportage.

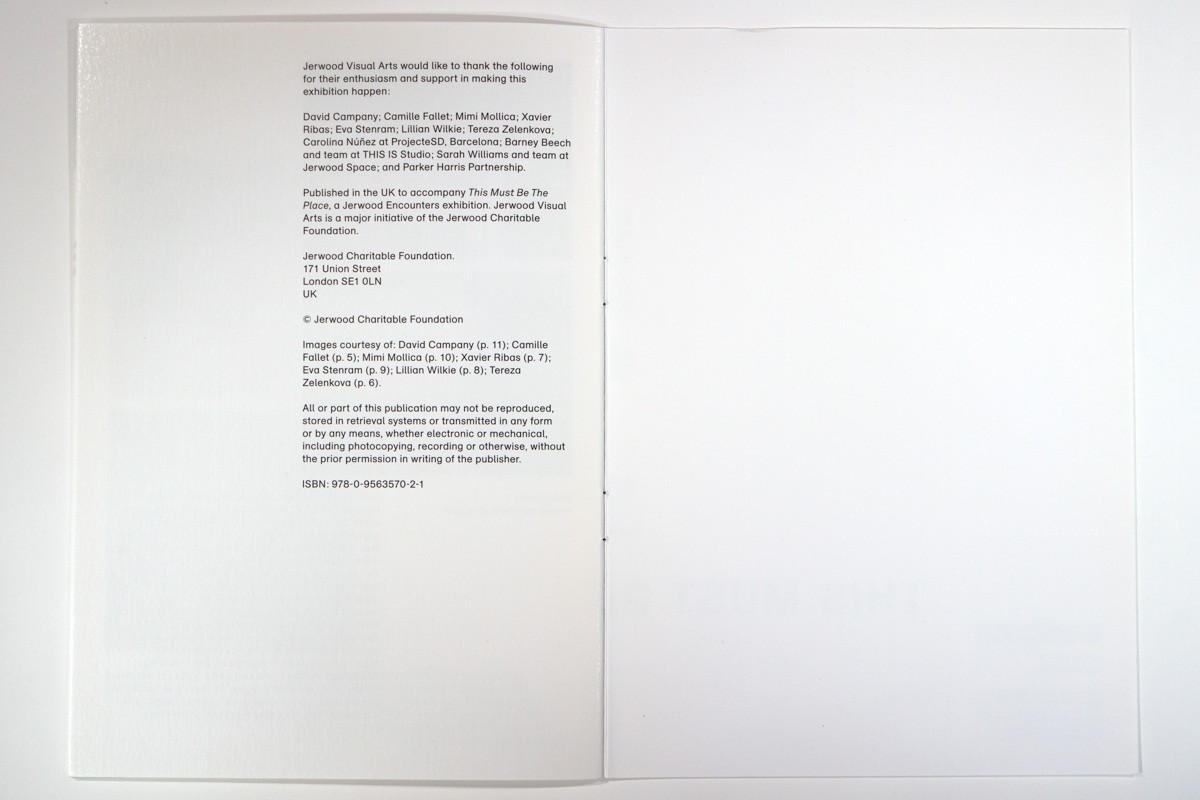

My own contribution is the film/photo projection One Way Street in China (David Campany, 2008). I spent seventy days in Xiamen and Shanghai, with my Mandarin-speaking wife and our daughter. While unpacking my bags I realized it was not the first time that I had brought on an overseas trip Walter Benjamin’s One Way Street, his aphorisms and observations on city life published in 1928. Why was it useful to be an Englishman in China with an eighty-year-old German text? The project was my attempt to answer that. I’ve always assumed Benjamin wrote it a paragraph a day, assembling a loose collection as he went along. So I took that as a model. With a simple camera that could shoot stills and reasonably good silent films I made a small piece of work every day. Of the seventy made, around twenty are presented here. In the 1920s there was much excitement at the prospect that one day making films could be as simple and as variable as writing. Current cameras and simple software have certainly made that possible. Each piece was sequenced the day it was shot using Apple Macintosh’s ‘Keynote’. It’s not even a proper filmmaking programme but it can be. I use it to make art, structure books and plan exhibitions, including This Must Be the Place.

1 This Must be the Place is the latest in a long line of one-off exhibitions in Jerwood Encounters – is there a sense of narrative between the Encounters or is each one an isolated example of artists practising today? How did the concept of this exhibition emerge?

I think the thread is ‘working processes’. The Jerwood Space is very interested in shows that somehow manage to make evident, if not through the works then through the curatorial selection, something of the way in which artworks come into being. Catherine Yass curated a photographic show which was very much about the ways the medium can be used as a form of ‘working through’, perhaps towards something else – a sculpture or film, or a more resolved photograph. I’ve gone in a related direction to look at the different ways images are edited and brought together into single bodies of work.

2 The exhibition focuses on a range of localities across the globe – was it a conscious decision to get a fair representation of international work? I’m not in a position to make a ‘fair representation of international work’ and I don’t know who is (there are certainly a number of curators who think they are or try to get into that kind of position and I’m fascinated by how they go about it, but it’s beyond my own capabilities). Around the time I was asked to put together a show I had just finished a number of projects in which the emphasis was on the temporality of photography and film. Meanwhile several artists and photographers I found really interesting were making responses to particular places. A road in Dakar, a disused piece of real estate in Barcelona, forgotten parts of Dresden, the Californian desert, for example. Straight away that conjures up something a little more ‘documentary’. I’m pleased to see that documentary has become an expanded and experimental form once again, which is as it should be. It had congealed into something very unproductive for a while. Although there is maybe only one person in the show who would consider themselves a documentarist, I think all the others would accept that there work has a productive relationship to documentary, put it that way.

3 We are all inherently linked to the places of our past and our present, and in many ways they shape our character – can you see a differentiation in the works of artists photographing their home area and photographing ‘new’ places? A doxa has grown up around the idea that creative work should begin with the familiar. ‘Start with what you know’, as they say on every creative writing course. There’s a huge presumption there that you are going to be able to make something interesting out of that. Some can but clearly it’s not going to work for everyone. And of course it may well be that you really don’t know what’s familiar until it’s confronted, contradicted or otherwise made unfamiliar in some way. Those who are able to start with what they know are able to see it as unfamiliar, which is to say unknown. As for the past, I agree with whoever it was who said it is a foreign country. Metaphorically for most; actually for some. This Must Be the Place includes a sample of London Photographs, Camille Fallet’s hugely ambitious photographic survey of vernacular London. He made it soon after arriving in England from France and it’s a project that could only have been done by someone fresh to the city. I don’t think a ‘Londoner’ would notice and photograph that way.

4 The two are inextricably linked, but how have you seen the relationship between art and photography evolve over the past five years? It’s going through a transition. After the inexorable rise of the large-scale tableau photograph I think there is a realisation that the medium has many more possibilities than that. There has been a quite extraordinary renaissance of the photographic book, for example. In the last few years books have been published to rival the great heights reached in the past, often by people who don’t give a fig about exhibiting. The book is enough for them. Then there are photographic projects that are conceived to work in different formats – in exhibition, in publication and online. There is also a realisation that much of the great photographic work of the past emerged from a hybrid working condition, between art and ‘applied’ photography. A number of the contemporary photographers I find most interesting are reinventing such spaces for themselves. Simply ‘being an artist’ may not be the best way to make good photographic work. It’s certainly not the only way.

5 There is a great emphasis in photography in capturing the ‘perfect moment’ – how does the exhibition address this? I’m not sure there is a great emphasis on the perfect moment these days. Of course it’s still there because photography has interesting ways of accessing or suggesting perfect moments, but it’s not the preoccupation for photographers that it once was. I think that began to recede a few decades ago. The reasons for this are really fascinating but too long to go into here. Suffice it to say one can’t rule out its return.

6 The atmosphere and understanding of place is a multi-sensory experience – were you able to incorporate the senses of sound, touch and smell into the exhibition also? Every exhibition has sound, touch and smell because visitors’ bodies have those senses. Is it there in the works themselves? You’re not allowed to touch the photographs. You can pick up and read some of the books. The video projections are silent (just moving and still pictures). Having just curated a couple of shows with sound I wanted to do something silent. The space of art finds sound much more of a challenge than movement. It’s something to do with the fact that we have eyelids but no earlids.

7 The exhibition also displays works and ephemera from those who have inspired the photographers, engaging in the history and the development of the medium – what contribution do you see new photographers giving to this narrative? That’s a really key question for me. I’m interested in curating shows that bring together contemporary and historical work. I notice a split – more visible in photography curating but still pretty widespread – between ‘contemporary shows’ and ‘historical shows’. Photography has an extraordinarily rich and varied past, perhaps so rich that it is frequently boiled down to a small handful of touchstones for today’s audiences. That’s a real shame because there are precursors for much of what is being done today. And we needn’t be scared of that. It’s a matter of finding what might be useful connections between the present and the past. I’ve just co-curated ANONYMES for Le Bal in Paris, a show about the depiction of anonymity in North American photography and film. There are new works presented for the very first time alongside pieces made in 2008, 2005, 2006, 1997, 1979, 1974, 1970, 1961, 1947, 1946 and 1938. Some works are by very famous artists, some unknown, some quite forgotten. It’s not always possible to do that. Jerwood Space asked me to curate a contemporary show but I’ve managed to sneak in a fascinating piece by Walker Evans, made in London in the 1950s. It’s a bonus for the historically-minded and sits in the show very nicely. I kept his name off the publicity.

8 I want to talk through each of the photographers individually, but whose work really stood out for you? I selected works that are formally very different from each other. That way they all have the potential to stand out.

9 Tereza Zelenkova’s work contrasts black and white, with colour photography – something that has occurred since the 1960s. Why do you think this contrast holds a continued fascination for photographers? Tereza works in black and white quite a lot, colour occasionally. Often it’s a way of making a photograph less historically specific, more ‘removed’ from reality. Up until the 1970s black and white had connotations of seriousness and on the whole artistically minded photographers avoided colour because of its associations with commerce. Of course that’s all changed now. Moreover I think a fluid relationship has been created by the new shooting and printing technologies. Colour and black/white used to have very distinct technical processes for shooting and printing, now they needn’t. My own work in the show slips in an out of colour too. There also a more profound point here. To shoot a colour photograph is to also shoot a black and white one. Every colour photograph contains its black and white equivalent. But you cannot derive a colour photograph from a black and white one. It’s not a symmetrical relationship. I suspect most of us sense this without knowing it.

10 The work of Xavier Ribas is ambiguous in its message – documenting without passing judgement in a manner unique to photography – how much does the viewer have to contribute to have a better understanding of the work? Photography is pretty good at showing and pretty lousy at explaining. Xavier works in a long tradition of topographic photography that makes a virtue of that tension. It goes right back via Robert Adams and Lewis Baltz, through Walker Evans to Eugene Atget and into the nineteenth century. Because photography evolved as a medium of documentation we often expect photographers to have, and to make, very clear statements. They need not. And many cannot.

11 Lillian Wilkie’s artist’s books show the accessibility of the medium, in delving deep into detailed examination of a place – was it difficult however to display these works in an exhibition format and still provide a complete view? Lillian’s suite of books is the result of walks made across Dresden, noticing details and weaving them together with fragmented accounts of the past. Her work alludes to the casual tourist snapshot but she’s a careful photographer. Precise and understated. It’s true that books are essentially unexhibitable. They need to be picked up, held, looked at and read. Lillian’s happy to let visitors do this but that’s unusual. How often to we see books sealed off in exhibition vitrines? It’s a real problem for exhibitions, particularly of photography. Not only is so much great work being made in book form but nearly all the great landmarks of photography’s past were publications, not exhibitions of prints. I’m not sure the museum or gallery can ever accommodate that but the effort must be made if photography is to be taken seriously.

12 Eva Stenram’s Pornography/Forest injects humour and kitsch into the exhibition – is it important to laugh at ourselves and the deified position awarded to contemporary art? It’s important to laugh at ourselves, but it’s not important to laugh at art. One can take it seriously without deifying it. There’s more than enough deification in the world right now. It’s interesting, one of the UK art magazines has just done a special issue on religion and spirituality. I was amazed to see usually pretty clear-headed thinkers repeating journalistic banalities such as ‘art museums are cathedrals for the secular’. Perhaps we need to be a bit more precise and vigilant about this deification business. Eva’s nature pictures are derived from internet porn sites. She downloads them and digitally removes the ‘action’. I wanted something in This Must Be the Place that didn’t quite fit, something that called the whole idea of ‘place’ into question. These are photographs of very particular places but the internet itself is a non-place.

13 Mimi Mollica’s work references the growth of street photography – which has seen an explosion of popularity with blogs taking over the internet – how do you see this work as developing from the works of the street photography greats such as Walker Evans and Robert Frank? And is this an inherently American format? Where you find streets you will find ‘street photography’. It’s not an American phenomenon. One of the things unique to photography is that it can be a form of hunting and invariably the pickings are richest in the street. But I am ambivalent about the rampant return of the genre, not least because so much of it is so generic: an empty sport in which too many are happy to make poor imitations of the unbelievably high standards of the past, while others settle for too little: ‘comic’ juxtapositions between people and the billboards behind them, grotesque gestures produced entirely by the shutter, third generation pastiches of ‘urban alienation’ (you know who you are!). There is a handful of people looking way beyond that, and I would include Mimi among them. His square format work from a new highway out of Dakar, shown here as a digital slide show, is the work of a photographer not trying to imitate anything but really struggling to find a form to articulate something significant about his subject matter. And if you can do that successfully and you are working in the street then you will have also pushed the genre forward, saying something significant about photography. It’ll never be pushed forward simply by those wanting to make ‘good street photographs’. That’s too narrow an aim.

14 Although all of the works in the show, including your own piece One Way Street in China, have an emphasis on place, in being made at specific historical moments they also have a relation to time. You mentioned at the beginning you were trying to get away from time. Not ‘get away from it’ exactly, just shift the emphasis. You’re right, all photography is temporal. But as you hinted earlier when photography addresses itself to particular places what results is a meeting between photography’s temporality and the temporality of those places. I think this is why so-called ‘landscape photography’ has also experienced something of a revival in recent years. For many contemporary photographers landscapes have the potential to combine a partially obscured past, a contested present and an unknown future. I have always had a secret suspicion that although photographers seek out subjects to photograph they are choosing ones that express something of their feelings for their own medium. It strikes me that photography itself seems rather beautifully suspended between its partially obscured past, its contested present and its unknown future.